October 27, 2017, 1:08 am

The author (left), John Proom, Iain Robertson and another, JMCS Glencoe bus Meet, 1957.Image RNCMy first acquaintance with mountains grew from flight from the dullness of weekends at home, especially Sundays, and fed on the romance of exploring unvisited crags and finding a place in a small history. I began with camping/hill-walking trips with friends in the Scouts, then learned to climb rocks on Craigie Barns, the little hill above Dunkeld, and soon joined the local mountaineering club in Perth. This functioned through day meets mostly. A Sunday morning bus collected us from points around town, took us to the mountains, and returned us in the late evening. Our far point on these excursions was Glencoe. As petrol rationing eased, and cars could be afforded, we added weekend outings to Derry Lodge in the Cairngorms and to the SMC Hut on Ben Nevis. In the school holidays I was able to reach Arran and Skye. I recall a week in Glenbrittle Lodge there in 1960 for 6 guineas all found. The publications of the SMC, and W.H. Murray’s Mountaineering in Scotland and Undiscovered Scotland defined the world I sought to master, and taught me how to behave in it.

After a few years of activity, I knew our mountains tolerably well, summer and winter, and loved them all. In a very small space, we found a great range of types of rock to climb, and mountain forms of all sorts, book-ended by the prickly Skye peaks and the rolling Grampian hills.I felt a strong sense of ownership – a common feeling among mountaineers. It has its drawbacks. We find it difficult to tolerate others who presume to own mountains. There is always some new enemy of beauty, solitude and free movement: deer-stalking, crop forestry, hydro-electric plants, ski facilities, and now giant pylons, electric fencing, and wind-farming. How dare these ignorant Barbarian users of mountains, animated by greed rather than love, intrude and despoil!

But if you take your place in this history, you are soon drawn in to the 'politics of the environment', as Malcolm Slesser put it. I passed my 40s and 50s in Committees, Councils and Trusts, and began to see the mountaineer in a different light – the user who takes the greatest pleasure from our hills, but who pays the least for the privilege; the user who demands free access, free carparks, free footpaths and bridges, yet deplores any financial easement granted to commercial use of mountains; the user who inveighs against wind-farms, but who built the first mountain wind-turbine at 700 metres in the bosom of Ben Nevis; the user who deplores the ugliness of other mountain uses, but who – in the recesses of his garish clothing – carries a phone that defaces hilltops with masts, and a GPS navigator that pollutes the skies with satellites.

Although my perception shifted during those years, so did mountaineering. There has been a loss of virtue. We were once an elite, which embraced Percy Unna's doctrine – 'the mountains shall not be made easier or safer to climb', which preached and practised self-reliance, and accepted the price of long approaches, river-drownings and deaths from hypothermia. We are now a mob, and the mob counts life as sacred, demands deliverance, and expects to pay no price, expect perhaps the price of a Guide who will ensure our safety, and carry our luggage up the hill.

Much has changed since I started climbing mountains, but the mountains are more or less the same, and the principles that regulate acquaintance with them haven’t changed unduly: boots, anorak, map, and compass work as just as well today as they did sixty years ago. The climbers – increasingly pagan, selfish, and hypocritical – still like to hear the 121st Psalm at their funerals. They get something from the hills that other parts of their life fail to provide. For me, and for thousands of others, our regular pilgrimages to the hills remind us that there are some things that don’t change, and that shared hardship and dependence on others for company and assistance still have a place in a world dominated by easy comfort and independent living. ![]()

Robin N Campbell: 2017First Published in The Geographer

↧

November 4, 2017, 2:20 am

Lakeland Fells: Delmar Harmood Banner-The Lakes Trust

The Climber

Climbing mountains was climbing

himself. From the summit

he could look down and see below

the problems he had left behind

Thoughts were like flowers on

the ledges, high up and far out,

the best needing to be plucked

dangerously and smelling of courage.

At night there was this mountain

above him, dark as the cave

of sleep he would enter and emerge

from tomorrow to resume his climbing.

R S Thomas

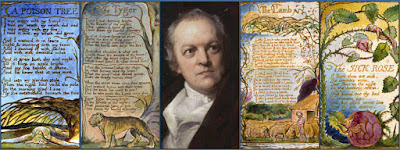

William Blake spoke of spots of time; those fleeting moments in life when one escapes the fetters of ‘mind forged manacles’ to express and experience humanity in its complete wonder; to be alive.

Unusually this was something which Blake had in common with Wordsworth and the Romantics. Where their paths split, where they went their separate ways, was with regards to their understanding of the point of it all. Where they differed so radically was on process and purpose : on how one gets to the point, who could get there and, in the end, what is the point?

The ‘point’ for Wordsworth was precisely that; to reach a place, far removed from the humdrum of daily life. A place where one could see all, and put things into perspective. The preserve of the ‘cultured elite’; of those who had the time, money and temperament to undertake the arduous process of inner reflection and personal betterment. To be ‘good enough’ to view and order the world from an elevated position of superiority.

In sharp contrast, for Blake achievement and identity was never about the individual, nor rooted in personal introspection; it had little to do with getting away from it all. No, for him, to be human was a much more expansive process. For Blake personal identity could only be expressed in terms of communal solidarity and action. That is, the extent to which we can only fully understand ourselves through shared purpose, collective appreciation and communal experience. How it is that we can only truly be, through, and with others. Ultimately, for Blake it is not about escape but about engagement.

From what I know of R S Thomas I strongly suspect that his sympathies were much closer to those of Blake than Wordsworth.![]()

By happy coincidence the day I received The Climber from a friend, I bumped into the re-printed article by Terry Gifford highlighting how narrow thinking by editors has squeezed the space for poetry within climbing literature. What is on offer here is less about poetry in climbing, but more about the poetics of climbing; the words we use to describe our experience, what this may say about how we make meaning out of climbing, what it includes and what it excludes. It is an attempt to develop Gifford’s proposition by exploring the inter-relationship between blinkered editors and a wider popular consciousness which I fear is constricted by its own vocabulary.

Back in 1984, Terry Gifford wondered ‘how far British climbing writing has emerged from the Rock and Ice era’. His question is as pertinent as ever and the poem by R S Thomas’s helps us address the question. I think that the poem highlights tensions and contradictions within language, forms of thinking and visualisation which still restrict our view of climbing. If we look carefully we can see how Thomas’s language is both beautifully evocative and yet slightly constricted within the confines of romantic language and sensibility. It is only at the summit where the experience is complete, the impression of escape and how insight is derived from courage in the face of danger.

This isn’t to say that these sentiments and evocations are invalid or of less worth, but simply to put them in context. The context of Blake, of what he anticipated would grow into commodity and universal empire. A restricted way of seeing; a way of being built on the muscular ideals of personal achievement, fortitude and conquest; of being the best – the perfect specimen. The key word here is restricted, not right or wrong. Blake simply recognised that this way of being was just that; one way; not, the way.

What strikes me most of all in this is that while climbing continually portrays itself as a counter culture of outsiders, it expresses itself overwhelmingly within the mainstream idiom. We may actually ‘talk’ more like the ‘insiders’ we often scoff. Whilst it is easy to track the extent to which the practice of climbing has escaped the constrictions of polite society and the amateur, it is less clear on how far our talking and writing has progressed. Rock and Ice prised open the doors of the Alpine Club many years ago, quite literally changing the face of climbing, opening it up, making it more democratic in the sense of its ‘membership’. But the extent to which our chatter both then, and since, has escaped the confines of mainstream constructs is less certain. I personally detect a strong continuity of romantic sentiment which both feeds and feeds into a wider set of climbing constructs which are perhaps not as counter as we imagine.

To start with, whilst Rock and Ice clearly pushed the boundaries in terms of who could climb, ‘talk’ about climbing remained firmly rooted in male white tropes, when men were men; rites of passage had to earned the hard way and apparently nobody took themselves too seriously. Later, whilst this hard edge of masculinity soften and more athletic forms of practice were celebrated, the vein of hardness remained as core stratum. Indeed it has continued to be a rich seam within the literature, often expressed as nostalgia for those times of hard training, hard climbing, hard partying and hard womanising. On top of this, familiar romantic tropes such as the savage beauty of nature, trial by ordeal and courage in the face of overwhelming odds have provided the scaffolding for much of the spoken and written word. To me this remains as strong today as it ever was. For sure the language has softened, but the underlying sentiments remain present and remain visible within our current self-preoccupation with process and the journey. Just to give one current example. I couldn’t help but notice the latest ‘big number’ headline on UKC recently - “E10 7a” (UKC 11/Oct). Reading the associated article, I was struck by what I interpreted as reticence : ‘for those interested in the numbers’. Perhaps a healthy ambivalence with regards to a perceived pressure to reduce a long and complex effort into a number; unease at the way in which numbers make good headlines in the same way that points make prizes. The climbing media and its editors are not totally responsible for this either. We can’t blame them for everything that is spoken and written.

Clearly there is much talk and many perspectives on climbing, but I think it is reasonable to suggest that one thing all these different conversations have in common is an insistence on climbing as counter culture. But I am left wondering how counter we really are? If we look carefully at our language then we see that we may be part of a counter culture which is almost wholly dependent on the language of the mainstream to articulate and describe itself. No wonder there isn’t any space for poetry.

Responsibility for where we are and where we go as a community of climbers rests on the shoulders of both the residents and those who purport to speak on our behalf. In this context I think it is great that the other Climber is seeking to add depth of analysis and breadth of coverage into its new format. I also chuckled this week to see that, characteristically, UKC appears to have risen to the challenge by re-defining “ESSAY” as no more than 3 paragraphs (UKC Oct 12 ESSAY: Why do Climbing & Mountaineering attract Outsiders?) . But it is easy to mock this lazy thinking. We should all think about our own language and how we can contribute to developing a more expansive and inclusive vision of climbing. ![]()

↧

↧

November 10, 2017, 1:13 am

![]()

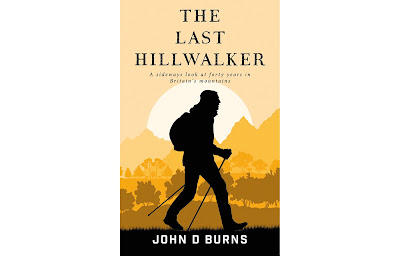

John Burns was a name that I was familiar with without knowing much about him. I’d seen the name crop up in the Twittersphere and on social media platforms without having much of a clue what his bag was so to speak. I knew he was based in Scotland so imagined a rugged Highlander who gained his spurs hacking up remote cliffs with a Slater's hammer and home made crampons. A smouldering tab hanging from gritted teeth framed within an ice crusted beard. Turns out that the author and I have more in common than I thought. A fellow Merseysider-albeit from the wrong side of the river- of a similar vintage and whose early footsteps into the great outdoors chimed with my own. The ill fitting clothing from Army and Navy suppliers, Boots guaranteed to inflict maximum pain . Tents which offered as much protection from the elements as Geisha’s bamboo umbrella.

And then there were the adventures.Those triumphs of hope over experience. Biting off more than you can chew and putting yourself and your unfortunate partner into situations where just staying alive becomes the ultimate aim and any thoughts of a simple fun day out spirals into chaos. But somehow, for most of us, we survived and lived to tell the tale, and it’s those triumphs and near tragedies which underpin The Last Hillwalker.

As you would expect, the early chapters describe how a gauche schoolboy slowly found his way into the world of mountain activities. The secondary school fellwalking and hosteling trips where in contrast to the stultifying restrictions and limitations placed on youth outdoor activities today by a zealous Nanny State, allowed youngsters an incredible amount of freedom and leeway. Hard to imagine today, a geography teacher propping up the bar while his charges set off alone and with limited experience on a lengthy mountain excursion that finishes in the dark!

In the intervening years since the freedom enjoyed by youngsters in the 1970‘s, outdoor education has either disappeared completely as cash strapped LEA’s sell off their mountain centres, or is so tightly managed and controlled by organisations who live in constant fear of litigation, as to make the experience an outdoor equivalent to painting by numbers.

But back to the book; the experience gained through these school excursions gave the author the confidence to tackle his first big outdoor challenge. The long distance Pennine Way which in those days really was a journey into hell! The cloying peat mud that could suck a divers boot off a misplaced foot, the seemingly endless rain, the miserable walker unfriendly villages that in contrast to today, treated scruffy young walkers as potential criminals.“ Mrs Pennyhassett... Call the police! ’.

Successfully completing the 280 mile route as a teenager in the 70‘s was truly a right of passage which announced that the author had arrived as a serious mountain man!

The freedom enjoyed by those who took their first mountain steps in the 1970‘s inevitably developed a ‘give it a go’ mentality, and for those like the author, fortunate enough to go to University, this attitude allied to the opportunities presented through Uni mountaineering clubs opened up new horizons. Offering the opportunity to develop new skills in new vistas like the Alps or Scottish mountains where the joys of rock and ice climbing were quickly learnt and exploited to the full.

Throughout the early chapters, the author counter balances his growing passion for the great outdoors with the social and political events at home. The 70‘s were after all a time of great upheaval in the UK with strikes, collapsing governments, three day weeks, the developing conflict in Ireland and mass unemployment. It is against this sombre backdrop that the author found escape in the hills. With Uni behind him he entered the Social Work profession and left Merseyside behind to further his career in Leicester before the opportunity arose for him to high tail it out of England and take a position in Inverness.

With the great Scottish ranges on his doorstep, it provided a wonderful opportunity to develop his winter skills and experiences. It was no surprise then that the author should eventually join a Highland mountain rescue team. Balancing a career with the social services with a mountain life is no mean feat and it was no surprise that as we enter a new century, the middle aged activist eventually steps off the gas. As relationships, family commitments and a peeling away of old comrades takes place. Something the single, childless activist cannot appreciate. Just how difficult it is to continue an active mountain life at the same level once a partner and children come on to the scene. For many a middle aged climber, they can continue their activity albeit to a lesser degree. However, many just gradually give up climbing and hillwalking altogether with many taking up new hobbies like the current craze for road biking.

By the time the author had hit his 50‘s, the mountain flame that once burned so brightly begins to take on a different hue. Those activities begin to take on a more mundane course as he finds himself guiding low level walks for the elderly and disabled. As his confidence and enthusiasm for hard core mountain activities diminishes, a new chapter begins. The writer discovers he has a talent for live performance and develops a career in stand up comedy and eventually as a thespian. Developing a one man drama surrounding ‘The Great Beast’...himself...Aleister Crowley. Mountaineer, libertarian, dark arts practitioner and all round bad egg! Well...at least according to The Daily Mail who labelled him,'The Wickedest Man in England!' The author is blessed in his role as Crowley by sharing his physical characteristics and quickly finds himself playing to sell out crowds up and down the country.

At the same time, he slowly rediscovers his passion for the mountains by reacquainting himself with that most Scottish of institutions, the mountain bothy. Feeling somewhat flaccid, overweight and lacking in physical gusto, slowly but surely his bothy campaign takes hold of his imagination and by the end of the book, the author is once again finding pleasure in the hills of home.![]()

This brief overview gives but a flavour of what lies within The Last Hillwalker and the reader will find excitement, human interest and humour running like a fast flowing Scottish burn throughout its 300 pages.

John Appleby:2017

↧

November 17, 2017, 2:16 am

I took a first tentative step towards the Ogre in the spring of 1968. I felt the need to go off climbing on the really big mountains of the world following on from my experiences in the Hindu Kush with friends from the Nottingham Climbers’ Club in 1967. I started to hatch plans to go overland to Pakistan with Dave Nichol and also Ian Clough. Ian suggested I invite Don Whillans to come along as leader. I wrote off to the Pakistani authorities exploring the possibilities of climbing on Gasherbrum III, Kunyang Chhish and the Ogre. The Ogre was top of the list as I’d just read an article in Mountain by Dennis Gray who had marked it up as a better proposition than Trango Tower. Unfortunately permission was not forthcoming but I remained interested.

In February 1969 I wrote to Jimmy Roberts at Mountain Travel in Kathmandu, enquiring if he thought there was a chance of not only climbing in Nepal but also Pakistan. Jimmy had recently been there trying to gain permission for the Ogre. He decided against it on account of the turbulent political situation for this was the time when the young politician Zul kar Ali Bhutto was gaining strength and support to oust Pakistan’s second president and first military dictator, General Ayub Khan.![]()

In July 1975, Clive Rowland, Rob Wood, Tony Watts, Bob Wilson, Ronnie Richards and I travelled out to Pakistan to climb Sosbun Brakk, a shapely peak near the head of the Biafo Glacier. We came out on a shoestring budget and with limited time enforced upon us by commitments to jobs back home, and in the case of Ronnie and I, to get back in time to join the SouthWest Face of Everest expedition (see the account of this trip to the Karakoram in my book Up and About, pages 358–360).

We flew out on Afghan Air to Kabul. At £180 return it was by far and away the cheapest air fare we could find. We then took buses from Kabul, through Jalalabad and the Khyber Pass to Rawalpindi. There we stayed with Buster Goodwin, once Colonel Eric Goodwin of the Indian Army, who had settled in Rawalpindi after a lifetime of service mainly amongst the Pathans on the NorthWest Frontier. In fact Buster, within a few minutes of meeting, sold us all a copy of his book Life Among the Pathans. ![]()

We were, as can be imagined when considering our time and financial constraints, doomed to disappointment, especially as there was an added factor ensuring our demise – the weather. at year there had been consider able dumps of spring snow on the Biafo Glacier and we simply could not reach our objective. After three days of wading through thighdeep snow, sometimes up to our chests, we gave up on our peak and turned the trip into a recce of the Ogre. We had already seen the upper part during our journey up the Biafo and now, with Clive’s local knowledge, we went back down the Biafo and turned left up the Baintha Lukpar Glacier on to the Uzun Brakk Glacier. We climbed some way up the peaks to the west of the Uzun Brakk from where we had excellent views of the south side of the Ogre.![]()

I had for the last few years, and especially after climbing Asgard right on the Arctic Circle of Baffin Island, thought about climbing big rock walls at altitude. Without any obvious plan in it I had taken to climbing big rock faces, first in the Alps and Dolomites during the 1960s, then in the 1970s in Norway including the Troll Wall, and in Yosemite Valley on El Capitan. These climbs had involved evermore technical difficulty, and on the big walls on Baffin Island there was the added challenge of subzero temperatures. The next logical step could be right here on the Ogre.

I was now familiar with the effect of climbing in the rarefied atmosphere up to 27,000 feet (8,230 metres) on Everest but, that had been on relatively easy, non technical snow slopes. Even so, I knew enough to appreciate that to survive at that level it was essential that everything that had to be done was second nature. It would be an interesting exercise, to say the least, to see if I could put the two together successfully: climbing steep rock high in the thin cold air at 23,000 feet. If that worked out I might just have time, before old age and decrepitude, to attempt the mighty West Face of Makalu up to 27,000 feet, and even the highest rock face of them all, the West Face of K2.

My only regret was that I had not started my high altitude apprenticeship earlier. There is a relatively narrow window of opportunity to climb technical routes at altitude. It can only realistically happen after a climber has accumulated bigwall climbing experience and also climbed at extreme altitude but early enough to ensure that he is still fit and strong enough to put it all together to make technical climbs up high.

Clive and I decided to launch an expedition together for the summer of 1977 hoping that the mountain would still be unclimbed. It had already been reported in Mountain magazine that an eight man Japanese expedition had attempted the Ogre in the summer of 1974. The climbers were from the Shizuoka Tohan Club and were led by Reisuke Akiyama. Team members were: Yukio Katsumi, Kimio Itokawa, Masamitsu Urayama, Tetsuji Furuta, Mitsuo Nishikawa, Takeshi Tsushima and Toshio Kasai. They set up base camp on the Uzun Brakk Glacier and attempted the South Face but an avalanche left two members seriously injured and essential items of equipment lost. ![]()

↧

November 24, 2017, 2:09 am

I know now, from my own experience, that your memory of youth gets sharper as you get older. Wandering about the Highlands it happens to me more and more, and nowhere more sharply recently than on Ben Nevis.I was passing the point where the half-way house used to be, and in my mind’s eye I saw a lad in short trousers and a lithe fair-haired man, their backs bent beneath bulging rucksacks as they made to doss down on the floor for the night.

The wee fellow’s neck ached under the weight of that sack. He hated it as much as his companion relished doing what few folk would want to do. Ritchie, a champion wrestler, weight-lifter and racing cyclist, prided himself on being a “sourdough.” He scorned comfort. An unemployed Clydeside plumber he sought the wilds.He and I had been travelling across country from getting off the train at Taynuilt and crossing on the ferry to Bonawe three days before. Now we were heading for Rannoch Moor, via the top of Ben Nevis and Aonach Mor and Aonach Beag.

It was bliss to get that bag off, get the Primus going for a “drum- up” and curl up on the floor. But continuous sleep was hard to come by for heavy boots kept thumping in—folk on their way to the summit to await the sunrise— unaware that we were on the floor until their eyes became accustomed to the darkness. As we went up in the mist and drizzle of the morning we met party after party coming down, all of them bedraggled and disappointed at seeing nothing for their effort. Conditions were still the same when we saw the Observatory building looming ahead, less of a ruin than it is today, even to a bit of lead roof remaining. Unpacking the tea-can I went off to find “Wragge’s Well” marked on our old map a short distance away. Ritchie gave me a compass bearing and was pleased when I returned with the means of tea-making.

What we didn’t know was that the ridge of Carn Dearg has got many climbers into trouble for it is difficult to hit on. Ritchie set off confidently and still continued on our rough compass bearing when the easy slope became rocks. Soon they were so steep we had to face inward for hand and footholds.Ritchie was enjoying himself, but I was frightened.

The drag of the sack was unbalancing me and I could visualise myself falling into the unknown void below. My legs were trembling and once I had to cry for help. Memory is vague now, but I have an image of snow patches and an immense scattering of pink boulders far below and away to our right the narrow ridge we were trying to find. A series of ledgeways led us to it.Once down on the Aonach Beag col, Ritchie scrapped the idea of humping the bags over the tops in favour of dumping them for a quick race up and down. I really enjoyed myself then, free of ballast. It was fun to be crunching over the ice-hard snow-patches lying in the hollows and then running back down the screes to our bags.

Little could I have guessed after that wet week with Ritchie that it would be the cliffs of Ben Nevis that would draw me back again and again in every season of the year. Or that the least enjoyable part of future days on Britain’s highest mountain would be the plod from Glen Nevis and the descent from the summit after a day on the longest rock climbs in Britain.And now here I was on Ben Nevis again with two young folk who knew as little about the mountain as I did on my very first ascent, and this time I was going to the top by the pony track on a promising morning of crisp visibility though a full thousand feet of mist still capped the summit.![]()

It was the astonishing weather variations between sea and summit which decided the Scottish Meteorological Society to build the first mountain-top observatory on Ben Nevis lying in the direct path of Atlantic storms. What Wragge had been doing was a feasibility study over a period of two summers, climbing the ben from June until October inclusive. The £4000 required to build the Observatory was raised in Scotland, as was the money for the pony track.Suddenly everybody wanted to climb Ben Nevis—over 4000 within a year. Many of them would arrive in Fort William by the West Highland Railway which opened in August 1894 bringing the mountain within easy range of the mass of the Scottish population. Trade in the town was brisk. A hotel was built on top to provide bed and breakfast for those wanting to stay for the sunrise, and there was serious talk of extending the railway from the town to the summit.

Talking about these things my young friends and I overtook the first climbers of the morning, a family in yellow oilskins, father and mother with a bright-faced wee girl roped between them. In foreign accent the man asked if I thought the weather would remain fine. “We turned back from here yesterday. We would like to climb up the highest peak in Scotland but perhaps it is too much for this little girl?” She was not quite six.“She’ll do it if you can keep her interested,” I told him. “Tell her about the wee house there used to be on the top—the highest in the whole of this country. Give her something to look forward to.”

They were from the flat lands of Holland.We broke off from the path after crossing the Red Burn to see what we could find in the way of mountain plants among the boulders; fir club and other mosses, alpine ladies mantle, starry saxifrages and the tiny least willow. No snow buntings singing as I had hoped, but I have a feeling they nest here. We were well in the mist at 3500 ft. and at 4000 ft. were on the unbroken snowfield between Cam Dearg and Ben Nevis which Wragge called “The Plateau of Storms”.

I used the compass now in this dimensionless world of white mist on snow, to keep on parallel course with the big cliffs which sheer away from the plateau edge for roughly a mile between here and the top of Nevis. Then suddenly came the proof that all was well: the big snow dome of the summit suddenly bulged in front of us, the mist pouring off north-eastwards revealing the black thrust of crags soaring to thick lips of snow cornice.Our spirits soared as colour Hooded around us and below us. There was green-shored Loch Linnhe, a ribbon of soft grey winding to the blue hills of Mull. Corpach on Loch Eil and the Pulp Mill on its peninsula looking like a white toy. Highland topography at a glance. Behind the deep cut of the Great Glen jumbled ridges stretched from Knoydart to Kintail and Glen Affric. There would be even more to see when we reached the top.Our first delightful surprise on getting there was to find the Dutch family already there. The wee girl said she wasn’t even tired and proved it by grabbing my ice-axe and digging furiously into the snow while we talked.They were amused when I told them about the Fort William man who claimed the first wheeled victory on Ben Nevis by pushing a wheel-barrow to the summit, followed in 1911 by a Model T Ford motor car which took three days to reach the Observatory, but a mere 2 ½ hours to return after a night cooling down.

At the news of the victory of the internal combustion engine over the steeps of the mountain a public holiday was declared in Fort William and a pipe band played to greet the entry of the motor car into the town. The man with the wheelbarrow was there trundling along in the procession. It was to be another thirteen years before the motor car could equal the wheelbarrow by going up and down in a day. That came in 1928 when a Model A Ford achieved the feat.We took a walk along the cliffs to identify the peaks stretching from Ben Wvvis to Ben Lawers, Schiehallion, Ben Alder and the high mass of the Cairngorms, the nearest approach to true Arctic terrain we have in Scotland and still very white after an exceptionally long winter and cold spring.

Sheltered by the modern “survival hut” which perches on what used to be the Observatory conning tower, I thought about the disappointment Wragge must have felt when the Observatory was built and he was refused the post of Superintendent which he wanted. But you can’t suppress a man of his pioneering spirit.He had been in Australia, and he went back there, getting his due as Government meteorologist and setting up mountain-top observatories on Mount Wellington and Mount Kodciusko. The world remembers him as its first long-range weather forecaster. He died in 1922.The staff of the Observatory was normally four and they seem to have got on comfortably together with little friction. Visiting students came to stay. One was C.T.R. Wilson, a Nobel Prize winner from Glencorse whose work played an important part in the development in nuclear physics. It was the optical phenomena shown when the sun shone on the clouds surrounding the hilltop that turned his thoughts to imitating them in the laboratory which led to 40 years of tracking atoms.![]()

Later, in 1892 they had to warn tourists not to hurl rocks down the cliff. An incredible thing had happened: a family from the north of England had scaled the 2000 ft. cliffs. In four days the Hopkinson brothers pioneered two of the great classics of Scottish climbing, Tower Ridge and Observatory Ridge. Strangely they wrote not a word in any journal about it.In March two years later a noted Scottish Mountaineering Club alpinist came with a strong party in March and made the first winter ascent of Tower Ridge which Collie described as being comparable with the Italian ridge of the Matterhorn—powerful praise and not over-stated. These great crags are a volcanic cauldron of lava which did not erupt but subsided inside a mass of softer material, its head changing the nature of the surrounding rocks.

It was erosion by moving masses of ice scraping away the softer which uncovered the inside of the mountain and made its lava the north-eastern outside we see today, a superb architectural form of ridge and spire, buttress and arête, gully and chimney. From below they look even more daunting than from above, so all praise to the Hopkinson brothers in finding two of the best natural lines.Among the early pioneers was Dr W. Inglis Clark, Scottish Mountaineering Club President from 1913—19. His name is remembered in the only true alpine cabin in Britain, situated below the Tower Ridge. Dr Clark built it to commemorate his son Charles, who died of wounds in Mesopotamia. It was opened in 1929. This year a large gathering of Scottish Mountaineering Club members plans to celebrate its 50 years of active service.

I’ve been looking back the record of the official opening of the hut on 31st March five decades ago. The time was 7 p.m. They had just eaten a splendid meal cooked on the club stove. It was snowing hard outside when the door was thrust open and in lurched two climbers in a state of near exhaustion. They had fallen from Observatory Gully, lost their ice axes, slid 600 ft. and were fumbling their way down when they saw a light beside them. Clark wrote: “Thus early our hut had justified itself in time of danger.”

Time of danger? In fact mountaineering accidents were very few on Ben Nevis until the sudden popularisation of the sport in the late 50s when the climbing revolution took place and gathering streams converged in all seasons. Accidents became commonplace- over 50 in two decades- many of the victims totally lacking any idea of what to expect on this most savage of Scottish peaks. There is less excuse for ignorance today than when Ritchie and I went up on our first visit.

How long should you allow yourself to climb Ben Nevis by the pony track? For comfort you want seven hours from Achintee or from the Glen Nevis Youth Hostel. Don’t be misled by the fact that runners in the Ben Nevis race, held on the first Saturday in September, will have to beat 1 hour 26 minutes 55 seconds to beat the record from the town park to the summit and back.Just remember that experienced fell runners regard the Ben Nevis race as the hardest in Britain, not just because it rises so sharply from sea- level to summit, but because of the roughness of it, and the severe jolting body and feet have to take on the descent.

August will see hundreds of climbers on any reasonable day setting off up the pony track to the top. if you are one of them, make sure you have some warm clothing and a pair of gloves, even if it is warm and sunny in Fort William. And your footgear should be stout and comfortable, not smooth leather soles, but with nails or cleated rubber to give a grip.Don’t be put off by mere mist for the upper part of the hill is well marked by cairns of stones. You may climb above the clouds or get the same kind of clearing as we did. But don’t be too proud to turn back if the conditions become too wet and stormy for comfort. Go back another day.The Big Ben is an experience not to be missed.Tom Weir: First published as 'The Big Ben' in The Scots Magazine-1979

↧

↧

December 1, 2017, 1:06 am

Making plans at Base Camp. L–R: Tut and I intend to climb the South Pillar; Nick with Chris, and Clive with Mo, are planning to climb up to the West Col together.The OGRE. Doug Scott. Vertebrate Publishing. £20.

Biography of a mountain and the dramatic story of the first ascent.

This book is the story of the Ogre in two parts, the first is concerned with its geological evolution and exploration from the earliest times, the second part is the story of the mountains epic first ascent.

The Karakoram has within its range, some of the world’s highest mountains, but also many of its most dramatic peaks in terms of difficulty to ascend and the Ogre is one of these. To those who are unlucky, and have never visited the Karakoram, it is hard to find words that do justice to the first sight of mountains such as the Trango Towers, The Mustagh Tower and K2 which impress on the climber as they walk into their glacial fastness. All is on the grandest of scales, and in an attempt to convey this, The Ogre begins with an explanation of the geological forces that have formed these incredible peaks. The book then moves on to detail an ancient history of exploration, putting into context the geopolitical and historical importance of the barriers to travel formed by the Hindu Kush, the Pamirs, and the Karakoram mountains.

The early explorers were driven by many different forces, some by conquest as in the campaigns of Darius the Great of Persia who as early as the sixth century BC conquered northern Pakistan, and just three centuries later the invasion by Alexander of much the same territory. I noted myself whilst in the Swat Valley how some of the local men still dressed in similar attire to classical Greek studies. The Karakoram on its northern- slopes spreads into Xinjiang, and it was passing through that territory that drove merchants and religious pilgrims, across the huge and perilous expanses of the Gobi and the Taklamakan deserts, following what became known as the Silk Road (a name coined by Von Richtofen in the 19th century). This was never a single pathway, for it diverted, moving west or north and south leading into Central Asia, India and Europe. And though detail of these events, are of necessity superficial, Scott does a good job in distilling down the essential early history of the region. My own favourite traveller story is that of the Chinese monk, Xuanzang (Hsuan-Tsang). He left what is now Xi’an in the mid-7th century to travel to India in search of Buddhist scriptures. He returned 16 years later, armed with 75 of these having travelled across some of the most challenging places on earth; the deserts and the Himalaya, travelling as far south as Sri Lanka. His adventures are told in the ever popular Chinese classic, ‘The Journey to the West’ and every school child in that country knows of these from the ongoing CCTV series ‘Monkey’. These have enlivened many a dull hour when travelling around China for myself.![]()

Strategic necessity then forced the surveyors such as Godwin-Austen deep into the mountains. And he was the first westerner into the environs of The Ogre (Baintha Brakk) in 1861 fixing its height at 23,914ft. It is interesting to note that where possible the surveyors always tried to find out the local name for any of the peaks they were interested in. Besides the surveyors there were still keen explorers appearing on the scene, most notably in 1887 the soldier Francis Younghusband; he made some significant journeys across China, and into the Karakoram but is now remembered most as the leader of the ‘1903 invasion of Tibet’ which like the Iraq war in modern times was the result of a failure of intelligence. After slaughtering with Maxim guns several hundred badly armed Tibetans, he had a religious experience on a hilltop above Lhasa, and spent a large part of his life thereafter promoting interfaith dialogue. However he was also a driving force after The Great War in the planning of the early British expeditions to Mount Everest.

By the end of the 19th century mountaineering was under away in the Karakoram, and one of the major figures in bringing this about was Martin Conway. Anyone who has read ‘The Alps from End to End’ or Simon Thompson’s modern interpretation of this will know what a forceful, entrepreneur and self publicist Conway really was. Marrying an American heiress, whose stepfather bank rolled him out on many of his schemes he nevertheless put together an outstanding exploratory expedition to the Karakoram in 1892. Amongst its members were Eckenstein the inventor of the 10point crampon, Bruce and Zurbriggen a Swiss guide. They made a journey up the Hispar and down the Biafo before reaching the Baltoro Glacier. However there was dissension in the ranks and Eckenstein who was keener to climb some peaks rather than exploration and mapping, argued with Conway and left the expedition. It is thought it was Conway who gave the ‘Ogre’ its name although there is some confusion over this, for a mountain nearby is now known to climbers as ‘Conway’s Ogre’, Uzun Brakk on the maps. His expedition was a first in many ways; Bruce a Gurkha officer and a future leader of the earliest attempt on Mount Everest, brought four of his soldiers with him, starting the tradition of employing Nepalese hill men; Sherpas on many future expeditions, and adding much cartographic detail to Godwin-Austen’s work, plus several equipment innovations, including beside crampons a lightweight silk tent designed by Mummery. ![]()

Post Conway exploration in the Karakoram quickened. The first expedition to K2 took place in 1902. This was led by Eckenstein, but it ran into difficulties from the first, when he was held under arrest by the deputy commissioner in Rawalpindi. It took him three weeks to extricate himself and rejoin the expedition, without any explanation as to this action. Subsequently both Aleister Crowley and Guy Knowles who mainly funded the expedition, believe that this had been done at the behest of Conway whose standing in the London establishment was by then forever rising. It is incredible in retrospect that Crowley was a lead climber on this first attempt on K2, for he became known as ‘The Great Beast 666’, involved in drugs, sex and black magic. During the expedition he even threatened Guy Knowles with a loaded revolver. Maybe Nick Bullock is right, ‘there just are not the original characters around in British climbing any longer?’ Nevertheless the expedition did add quite some knowledge about the mountain and its approaches.

Scott makes a swift revue from thereon of developments in the Karakoram over the next period as more and more parties arrived to explore and climb its mountains. One such, were the American couple, the Bullock Workman’s, Fanny and Hunter. In eight visits between 1898 and 1912 they walked more and climbed more of the mountains than any other party hitherto. In 1909 the Duke of Abruzzi led the first of many outstanding Italian expeditions into the Karakoram. Making determined attempts on K2 and reaching a height of 24,600feet on Chogolisa, but being unfortunately dogged by bad weather throughout their stay. Vittorio Sella was the photographer on this expedition and his black and white prints of the peaks of the Baltoro region and of K2 inspired generations of future climbers.

The Italians were back in 1929 and 1930 exploring in several areas of the range, surveying and mapping and a Dutch couple the Visser’s made four expeditions in the eastern Karakoram. In 1937 Shipton and Tilman undertook a four month sojourn in the range mapping and exploring and Shipton returned in 1939 with another strong surveying and mapping team, who with great relevance to The Ogre story, produced an accurate map of the Biafo and the Uzun Brakk glacier systems. The stage was now set for the post war period of rising climbing standards, equipment innovation, and knowledge of the importance of altitude acclimatisation that allowed for attempts to be made on the Latok Peaks and The Ogre. It is thought its local name, Baintha Brakk means ‘The Rocky Peak above The Pasture’. ![]()

The author having rattled through these early explorations of the range, in Part two concentrates on the history of the attempts and at last the successful ascent of The Ogre by himself and Chris Bonington. The first to try in 1971 was a Yorkshire expedition led by Don Morrison and including Clive Rowland, who spotted a route up via the South West spur leading to the West Col. From where it might be possible to climb the West Summit of the mountain, but also to gain the slopes leading to the final rock tower of the main summit, which has been re-surveyed as 23,900 feet. Like many other expeditions to the Karakoram they were stopped by a bad run of inclement weather. Over the next six years several expeditions explored around the Latok peaks and the Ogre, and inevitably in that era most were Japanese. Although Don Morrison returned in June 1975 his party ran into serious porter problems, and ended by trying to in relays from Askole, which is now the road head, to carry in their own equipment to the Ogre base camp. They soon realised that this left them not enough time for a realistic attempt on the mountain, and so they turned their attention to three more accessible peaks nearby. In 1976 a strong Japanese party reached the West Col via the South West Spur and climbed some way along the west ridge, but for some unexplained reason abandoned this obvious route to the summit. And so the scene was set for Scott and his party made up of Clive Rowland, Paul ‘Tut’ Braithwaite, Mo Anthoine, Nick Estcourt and Chris Bonington in 1977 to make their attempt to climb The Ogre. They were a part of a golden age of British Himalayan climbing, and few parties have left the UK with such mountain experience behind them.

Initially the party split, Scott and Braithwaite set out to attempt the imposing south pillar of the mountain, whilst the other four concentrated in following the South West Spur. However climbing in the Himalaya is ever-dangerous, and whilst climbing a gully leading onto the south pillar, Scott dislodged a rock which ploughed into Braithwaites leg, immobilising him for the rest of the expedition and leading to a first crawl down by him back to Base Camp.

Meanwhile the other four had made good progress in climbing the South West Spur, and in typical fashion Bonington supported by Estcourt, made a dash for the summit. Reaching the mountains West Peak but being forced by technical difficulties to retreat from climbing on further to attempt the huge summit block, protecting the mountains summit. All then returned to Base Camp to recuperate. After which Rowland, Anthoine, Bonington and Scott climbed back up to the West Col. During all this activity they were blessed by unusually good weather, and to cash in on this as soon as possible Scott and Bonington set off for another summit attempt.

They made good progress in this, and after some tricky ridge traversing, reached the final summit block, which composed of marvellously sound granite, reminded Scott of his climbs on Yosemite’s El Capitan. The climbing from thereon demanded some of the hardest aid and free climbing then achieved in the Himalaya; however all did go well and they reached the summit. But it was on the descent from this that the meat of the story develops. On the way up the summit pillar, they had needed to make a huge pendulum to reach a crack system, and in reversing this Scott swung off wildly into space slipping on verglas, and hammering his legs by the impact at the end of his trajectory. Hanging on the ropes he realised he had fractured both legs. Somehow he and Bonington managed to recover from this and began to abseil back down the mountain. However they ran out of daylight and had to spend the night cowed together bivouacking on a tiny ledge. Next day they continued abseiling and on reaching the ridge leading back across to the West summit they were met by Rowland and Anthoine. Somehow with their unstinting support and help Scott managed to crawl back along the knife edge ridge to an ice cave they had cut below the West summit. But then the weather broke and what followed is one of the great survival stories of mountaineering. They ran out of food and after days holed up in the ice cave decided they must descend, despite a blizzard blowing outside.

This descent developed into a fight to survive; and due to a misunderstanding during this, on one of the abseils, both Scott and Bonington almost shot off the end of the ropes into space and oblivion. Chris unfortunately fractured his ribs during this happening. This epic lasted for days, including Scott needing to crawl all the way down the glacier and moraine system to reach Base Camp.

On arriving at Base Camp they were gob smacked to find it empty, for Estcourt (who had developed a serious throat infection) and Braithwaite believing their team mates had perished, had on the arrival of porters from Askole set off for home to relay the sad news of their friends demise. Mo Anthoine immediately set off, and by almost none stop moving and jogging managed to intercept them before they had managed to mistakenly post their companions as deceased to the outside world. It was fortunate that this had not happened today, for with solar panels, and mobile phones this false news would have reached the media, before it could be corrected. They returned with the porters from Askole, and after fashioning a stretcher, these Balti hill men carried Scott down some of the roughest terrain, to where a helicopter could pick him up and drop him into hospital. However a final twist to the story is that on this journey the helicopters engine stalled; and it crash landed on its approach. So it was to be several days before another replacement chopper could be found to go and pick up Chris who remained in agony with his damaged ribs.

A postscript to this impressive feat of survival is that the real heroes of the epic, Clive Rowland and Mo Anthoine who shepherded both Bonington and Scott off the mountain received little or no plaudits in the press reports for their part in saving the lives of their companions, who would not have made it to safety without them. Fortunately, even though it is now 40 years since the epic on the Ogre, both Chris and Doug in a series of lectures around the UK this winter, at this anniversary are both attempting to put the record straight by highlighting just how much they owed to Clive and Mo for a safe return, who unfortunately is no longer able to receive their heartfelt thanks having died of cancer some years ago now. ![]()

This book deserves to become like Touching the Void, Into Thin Air and Annapurna and be regarded as one of the great classical survival stories of our sport. Photographically it is well illustrated, and though in fact it is only a slim volume considering the history it covers, just for the pictures alone it is worth the purchase price. I understand Doug intends to follow this up with similar volumes about the other mountains he has been associated with in his long mountaineering career; Kanchenjunga, Makalu, K2, Nanga Parbat, Everest etc. If they are as good a read and production as The Ogre they will all I believe become accepted as yet another outstanding effort by someone who has put back into the mountain world more than he has taken out. I am thinking of his charitable initiative, Community Action Nepal which has done such good works in Nepal, building schools and hospitals in some of its remote mountain regions, and organising a safe and hygienic water supply for the Karakoram village, Askole as by way of his thanks to its denizens who carried him down to safety in his hour of need. Dennis Gray: 2017 Images supplied by Vertebrate Publishing

↧

December 8, 2017, 1:12 am

![]()

On the morning of the 28th we issued from our hotel. A pale blue, dashed with ochre, and blending to a most delicate green, overspread a portion of the eastern sky. Grey cumuli, tinged ruddily here and there as they caught the morning light, swung aloft, but melted more and more as the day advanced. The eastern mountains were all thickly covered with newly fallen snow. The effect was unspeakably lovely. In front of us was Snowdon; over it and behind it the atmosphere was closely packed with dense brown haze, the lower filaments of which reached almost half-way down the mountain, but still left all its outline clearly visible through the attenuated fog.

No ray of sunlight fell upon the hill, and the face which it turned towards us, too steep to hold the snow, exhibited a precipitous slope of rock, faintly tinted by the blue grey of its icy enamel. Below us was Llyn Mymbyr, a frozen plain; behind us the hills were flooded with sunlight, and here and there from the shaded slopes, which were illuminated chiefly by the light of the firmament, shimmered a most delicate blue. This beautiful effect deserves a word of notice; many doubtless have observed it during the late snow. Ten days ago, in driving from Kirtlington to Glympton, the window of my cab became partially opaque by the condensation of the vapour of respiration.

With the finger-ends little apertures were made in the coating, and when viewed through, these the snow-covered landscape flashed incessantly with blue gleams. They rose from the shadows of objects along the road, which shadows were illuminated by the light of the sky. The blue light is best seen when the eye is in motion, thus causing the images of the shadows to pass over different parts of the retina. The whole shadow of a tree may thus be seen with stem and branches of the most delicate blue. I have seen similar effects upon the fresh névés of the Alps, the shadow being that of the human body looked at through an aperture in a handkerchief thrown over the face.

The same splendid effect was once exhibited in a manner never to be forgotten by those who witnessed it, on the sudden opening of a tent-door at sunrise on the summit of Mont Blanc. At Pen-y-Gwryd Busk halted, purposing to descend to Llanberis by the road, while Huxley and I went forward to the small public-house known as Pen y Pass. Here our guide, Robert Hughes, a powerful but elderly man, refreshed himself, and we quit the road and proceeded for a short distance along a cart-track which seemed to wind round a spur of Snowdon. ‘Is there no shorter way up?’ we demanded. ‘Yes; but I fear it is now impracticable,’ was the reply. ‘Go straight on,’ said Huxley, ‘and do not fear us.’ Up the man went with a spurt, suddenly putting on all his steam. The whisky of Pen Pass had given him a flash of energy, which we well knew could not last. In fact, the guide, though he acquitted himself admirably during the day, had at first no notion that we should reach the summit; and this made him careless of preserving himself at the outset. Toning him down a little, we went forward at a calmer pace. Crossing the spur, we came upon a pony-track on the opposite side. It was rendered conspicuous by the unbroken layer of snow which rested on it. Huxley took the lead, wading knee-deep for nearly an hour. I, wishing to escape this labour, climbed the slopes to the right, and sought a way over the less loaded bosses of the mountain. ![]()

My own heat sufficed for a time to melt the snow; but this clearly could not go on for ever. My left heel first became numbed and painful; and this increased till both feet were in great distress. I sought relief by quitting the track and trying to get along the impending shingle to the right. The high ridges afforded me some relief, but they were separated by cwms in which the snow had accumulated, and through which I sometimes floundered waist-deep. The pain at length became unbearable; I sat down, took off my boots and emptied them; put them on again, tied Huxley’s pocket handkerchief round one ankle, and my own round the other, and went forward once more.

It was a great improvement— the pain vanished, and did not return. The scene was grand in the extreme. Before us were the buttresses of Snowdon, crowned by his conical peak; while below us were three llyns, black as ink, and contracting additional gloom from the shadow of the mountain. The lines of weathering had caused the frozen rime to deposit itself upon the rocks, as on the tendrils of a vine, the crags being fantastically wreathed with runners of ice. The summit, when we looked at it, damped our ardour a little; it seemed very distant, and the day was sinking fast. From the summit the mountain sloped downward to a col which linked it with a bold eminence to our right.

At the col we aimed, and half an hour before reaching it we passed the steepest portion of the track. This I quitted, seeking to cut off the zig-zags, but gained nothing but trouble by the attempt. This difficulty conquered, the col was clearly within reach; on its curve we met a fine snow cornice, through which we broke at a plunge, and gained safe footing on the mountain-rim. The health and gladness of that moment were a full recompense for the entire journey into Wales. We went upward along the edge of the cone with the noble sweep of the snow cornice at our left. The huts at the top were all cased in ice, and from their chimneys and projections the snow was drawn into a kind of plumage by the wind. The crystals had set themselves so as to present the exact appearance of feathers, and in some cases these were stuck against a common axis, so as accurately to resemble the plumes in soldiers’ caps. It was 3 o’clock when we gained the summit. Above and behind us the heavens were of the densest grey; towards the western horizon this was broken by belts of fiery red, which nearer the sun brightened to orange and yellow. The mountains of Flintshire were flooded with glory, and later on, through the gaps in the ranges, the sunlight was poured in coloured beams, which could be tracked through the air to the places on which their radiance fell.

The scene would bear comparison with the splendours of the Alps themselves. Next day we ascended the pass of Llanberis. The waterfalls, stiffened into pillars of blue ice, gave it a grandeur which it might not otherwise exhibit. The wind, moreover, was violent, and shook clouds of snow-dust from the mountain-heads. We descended from Pen-y-Gwrid to Beddgelert. What splendid skating surfaces the lakes presented— so smooth as scarcely to distort the images of the hills! A snow-storm caught us before we reached our hotel. This melted to rain during the night. ![]()

↧

December 15, 2017, 2:35 am

Will Yo' come O Sunday Mornin' Fo a Walk O'er Winter Hill?

Ten thousand went last Sunday But there's room for thousands still!

O the moors are rare and bonny An' the heather's sweet and fine

An' the road across the hilltops is the public's — yours and mine.'

Allen Clarke, Winter Hill Mass Trespass.1896

It was the Kinder Mass Trespass of April 1932 that became immortalised in the struggle for `Rights of Way' over England's upland: Benny Rothman cycled from Manchester to the Peak District (as it became in 1951) to lead the march on to the moors, and thence into jail. The historic events in Bolton 100 years ago last year were almost forgotten, until re-discovered by Paul Salverson in his book Will Yo' come O 'Sunday Mornin' (1982). More overtly than the battle for Kinder Scout, politics played its part on Winter Hill, as the popular uprising was diverted into a struggle between the 'Bolton Socialist Party' and a local squire —the outcome perhaps inevitable in Victorian England. A glorious early September Sunday morning in 1896 saw a surprisingly large crowd gathered at Halliwell Road (barely a mile north of Bolton Town Hall), fired by speeches from the soapbox of William Hutchinson, Joe Shufflebotham and the doughty Boltonian journalist, Solomon Partington. Mill workers and hand loom weavers flocked from the terraced houses that crowded off the main street. Many in Sunday best, they rubbed shoulders with grimy coal miners from nearby pits, as the march grew to ten thousand strong as it reached the Ainsworth Arms, at the edge of town.

Emerging in jubilant mood from Halliwell Road, the long line passed Ainsworth's Bleach Works, then Smithills Hall (imposing residence of the other protagonist, Colonel Richard Henry Ainsworth), on the steady rise where Smithills Dean Road bolts arrow-straight for Winter Hill. The crossing of Scout Road marks the edge of Smithills Moor, as Coal Pit Road continues towards the summit, before contouring to the hill farms. At its high point, a track heads hard across the dark chocolate peat and heather-clad moor; its junction still marked by the original gritstone gateposts quarried from the moor. There the Colonel's men and local constabulary made their stand. Now celebrated by a handsomely carved stone, 100 years ago it saw a dramatic confrontation, where the ancient route to the summit ( 1500') was barred. After the invigorating march from the steaming mills of Halliwell, the ramblers were in no mood to be thwarted.

The Bolton Chronicle reported “... a scene of the wildest excitement...' and 'Amid the lusty shouting of the crowd the gate was attacked by powerful hands... short work was made of the wooden barrier and with a ring of triumph the demonstrators rushed through into the disputed territory'. In the melee, Inspector Willoughby dived over the drystone wall as Sergeant Sefton fielded the flying gritstone. Gamekeeper Watch's son was knocked over, relinquishing his precious list of names, plus hat and mackintosh, whilst another gamekeeper was ignominiously ducked in the ditch. ![]()

equivalent would make a national figure in a libel trial wince... A number continued down to Belmont village, to surprise the locals and, no doubt, delight the landlord of the Black Dog. As the Bolton Journal reported, 'Thus ended a demonstration... many returning to the town, and the remainder besieging the local hostelries... The demand was said to be so great that the wants of the hungry and thirsty ramblers could not be satisfied...' The next Sunday morning, despite inclement weather, (‘miserably wet' ) according to the Chronicle), again attracted huge support, and as the deluge cleared, the steam rising from the walkers rivalled that from the mills!

But the movement's denouement was nigh — the Colonel now entered the fray, counter attacking with devastating effect, isolating and issuing writs by the score,and as promised help failed to materialise, the Bolton Socialist Party slipped quietly away. Back in 1801 the Ainsworth family were already wealthy enough to purchase Smithills Hall and Moor for a princely £21,000. Later, their ownership of the Bleach Works allowed the Colonel to indulge

his love of grouse shooting, leading to the closing off of Smithills Moor. At the trial the defence called 44 witnesses but still lost the day, despite providing much amusement when William Fletcher, itinerant bricklayer,described his use of Coal Pit Road and stops at Black Jack's, (the moorland cottage of Luke Morris, who sold gingerbread with `free ale’ to subvert the licensing laws). One day, Luke tossed a loaded pistol into the fireplace — demolishing the cottage. So, it was left to Solomon Partington to repeatedly issue protest pamphlets against the Colonel, until the journalist finally retired. ![]()

Henry Tindell: 1997 . First published in High-May 1997 as 'Mass Trespass Winter Hill-1896

↧

December 22, 2017, 3:35 am

I'm taking a break until the new year so thanks to everyone who has contributed to the site or even just dropped in occasionally to see what's going down hereabouts. Have a non too stressful holiday and here's to 2018 being a little less fraught and downright crazy as recent years have been! As one of my heroes Edward Abbey once said...'"May your trails be crooked, winding, lonesome, dangerous, leading to the most amazing view. May your mountains rise into and above the clouds.'Peace Out. JA

↧

↧

![]()

I for one, and I suspect I am by no means alone, disagree with the protestor's argument. The aesthetic in wild country is not just about being there and looking at it, but it's also about the interaction of the person with that environment as he or she travels through it. That interaction is based mostly on the intrinsic satisfaction of experiencing an ever open skill in an ever changing challenge. Surely the satisfaction of some peak or other is not to be found in 'one is there' but in 'one got there'? How one got there, the nature of the challenge, is a choice that the individual makes — one that is supposed to be a key element of all wild country challenges — that the individual carefully assesses what level and type of challenge to undertake and satisfaction is gained by the meeting of that challenge.

There need be no reference to others, or rather one's rank in relation to others. The challenge for one person is as meaningful, as difficult and as close to the limit as any other person's challenge. The nature of that challenge in wild country is normally a combination of the mental and the physical. It is the latter that offers most scope for manipulation. One can choose a sustained strenuous route, one with a desperate bouldering move or a route of technical finesse. A day in the hills can be long, remote but with little technical difficulty or it can be short, sharp and requiring great technique. Why not, then, have fast days or trips — the speed at which one moves through this wilderness challenge is of great consequence in the level of difficulty of that challenge: it usually makes the challenge more difficult but not always so.

I have found, and I'm sure many others have also, that the challenge that suits me is not one of the maximum technical difficulty (a relative concept) but of travelling at speed through a hostile environment of lesser technical difficulty. There is great pleasure to be obtained from 'flowing quickly' through difficult terrain; there is great beauty in travelling fast along Crib Goch, the Skye Ridge or the West Ridge of the Salbit. One must plan the route ahead while travelling at speed over concentration demanding terrain, develop the ability to scramble blind over rock while searching out the footholds three or four moves ahead. In caves the art is all about working out rapidly and in advance the best way of tackling any obstacle or passage shape ahead; lots of different approaches will work of course but there is only one perfect solution and that is the one that guarantees speed, for there has to be great efficiency of movement if speed is to be maintaned. ![]()

One doesn’t have to be a fell runner or speed climbing competitor to get enjoyment from moving fast. You don’t even have to be fit,though undoubtably you will be in time. One needs to be able to jog over hilly country,develop some agility,have a keen eye for route choice and navigation and think carefully about equipment. There is little more pleasurable experience on rock than to solo long easy routes without stopping. To flow from hold to hold up Troutdale Pinnacle or Commando Ridge. To arrive at the top of the Gervasutti Pillar one and a half hours after leaving the glacier, unencumbered by a heavy sac, is pleasurable, satisfying and an eminently suitable way to tackle such a climb.

In the Peak District the route of Tanky's Trog, probably the best moorland race of all, is an absolute delight in its challenging simplicity; get from Marsden to Edale as fast as possible passing by Torside and the Snake Inn — a great, almost straight, point to point route with a multiplicity of major and minor navigational and route choice variations. Every second a fresh micro problem is presented.Whether the heather or the peat is fastest, whether the wet winding grough or the up and down of the straightline peat hag route is better. At the same time major decisions are calculated; does one take the route over Black Hill or contour it to the west, and all the time every stride must be smooth, efficient and flowing. Great complicated bumpy areas make ideal go faster challenges- try the ridge between Ennerdale and Wasdale, either going over the lumps such as Pillar and Kirk Fell, or traversing them. The best (i.e. fastest) route is tremendously complex and rarely obvious. Routes through the Howgills from east to west, (or vice versa), or on a smaller scale the lumpy rocky areas of the Lakes like that around Watendlath provide superb moving fast challenges through enticing bumpy country with constant decision making.![]()

↧

January 12, 2018, 1:39 am

If the doors of perception were cleansed, everything would appear to man as it is, infinite William Blake.

Two books recently published are focussing a new interest in the Karakoram Mountain Range; ‘‘The Ogre’ by Doug Scott and ‘Karakoram’ by Steve Swenson, the first by Vertebrate and the latter by The Mountaineers; (published in the USA-available in the UK via Cordee). The ‘Ogre’ has been well reviewed in the UK, but ‘Karakoram’ less so. It is a first person story of the authors 15 visits to the range, during which he amassed an outstanding record of ascents, plus the inevitable failures and epic retreats. Set against the cultural and political background of Pakistan during the almost three decades in which these climbs took place; a period of ever increasing tension caused by the Kashmir conflict with India, and the growing threat of Islamic fundamentalism and terror. It is in explaining and detailing the history of these events, and their affect on the local peoples of the Karakoram, that I found this book to be above the common place of such expedition fare.

I cannot compete with Swenson’s fifteen journeys to the Karakoram, for I have only been there on four occasions, but like him my own experiences in these incomparable mountains, can still bring from my memory bank, days (and nights) spent amongst peaks with magic names like The Trango Towers, The Gasherbrum’s, and Masherbrum.

My own experience in the range began when leading a trek to K2 Base Camp in 1989. The recalls from this are still raw, for by the time we reached Concordia (at approx 4600m), the famous glacier basin with its almost unbelievable dramatic mountain setting, and its iconic view of K2 and the surrounding peaks, I was almost bushed out. One of our Party, had become ill, and from about a section of the trek on the Baltoro glacier beneath the Mustagh Tower, two of the Balti porters and I had to take it in turns to support him physically. Fortunately after a couple of days rest on reaching Concordia he made a good recovery. I was feeling much the same, until scoping from our camp, scanning the slopes of Broad Peak (8051m) looming almost directly above us, something caught my eye which could only be human movement. Watching this for some time I realised it was a party in distress, and they needed help, and fortunately as our Sirdar Hussein had previously been with an expedition to this mountain and knew a safe route through its ice fall, we quickly readied and set forth to climb up the flanks of the peak to render what help we were able.

Some hours later we were within shouting distance of the stricken party, initially believing them to be Spanish but as we reached them, we found they were three Mexican’s; two females who were supporting a male climber held between them. They had descended from high on the mountain, from whence their team member had developed pulmonary oedema in a high camp 1600m above our heads. The women had more or less carried their companion for most of that distance, down some dangerous and difficult terrain. A truly impressive feat!

Hussein had along with him another Hunza, and they took over supporting the sick man to give the Mexican ladies a rest. However they soon tired and Marguerite the strongest of them and I then moved in to replace the others. I found this exhausting, but as we quickly lost height, it became somewhat easier. The Hunzas took over again to get the patient through the ice fall as I went on ahead to reach our camp, and to alert our Doctor, an American Peter Stone to be ready as soon as the patient arrived. Fortunately he had all that was needed, a comprehensive medical chest and some emergency oxygen. By the next morning the sick man was sitting up on a bed of sleeping bags, in our Base tent, and quaffing the hot drinks we prepared for him.

I have often wondered why so many climbers suffer altitude problems on Broad Peak? One such was a friend Pete Thexton, a Doctor himself who also developed oedema but unfortunately in a period of bad weather, was unable to descend and who died in a high camp. It seems that because of its reputation as a technically easy peak, climbers tend to move very quickly into the so called ‘death zone’. And I found that moving up so quickly helping the Mexican’s in their need, to a height well over 5000m was totally shattering physically.

So many memories remain from my four Karakoran visits, including meeting Mark Millar near Hushe, retreating after an attempt via a new route on the flanks of Masherbrum, as he was heading back to Islamabad to catch a plane to Kathmandu, to meet up with team mates for an attempt on Makalu ll. We said our goodbyes, but sad to report a few days later, he and his party perished in a PIA plane crash in the hills above Nepal’s capital. However most of my Karakoram memories are happy ones and an instance of this is the day we organised on a green sward, under Masherbrum, the ‘Hushe Olympics’. Climbers/Trekkers versus team Balti. The tug of war event became larger and larger in participation using a 60m rope. In the end the sheer number of locals prevailed, leaving team Climber spread-eagled on the ground.

But a Nanga Parbat trip (8125m), the 9th highest mountain in the world dominates at present my thinking from those days. This, the western bastion of the Karakoram boasts the largest mountain faces in the Himalaya, its southern aspect holds four kilometres of height above base. Its four deep and previously inaccessible valleys set around the Peak meant that the villagers residing in them all spoke different languages and even today are suspicious of outsiders. My visit to the northern, Rakhiot side of the peak in 1990, when I led a trek/climb to Julipar peak on the eastern flank of this huge face bears this out. Failing to reach the summit of this mountain, due to bad weather, we crossed over by a pass of that name into the upper environs of the Diamir, descending down into the shelter of the Patro valley. ![]()

Although what happened there on the night of 22nd June was widely reported, there has been little follow up and understanding of the disparate cultural and political forces at work in that area of the Karakoram. The Diamir Face, particularly the Kinshofer route has become the most popular way to access the summit of Nanga Parbat, and fortunately as the weather had been settled in that period most of the climbers, were in the High Camps. But 12 people remained in the Base that night when 16 armed militants, dressed in the uniform of the Gilgit Baltistan Scouts, arrived in the camp guided there by a local. This irregular military unit was formed by the British in the latter part of the 19th century and was based in Gilgit, hence its original name, Gilgit Scouts. On Independence it was merged with The Pakistan Army, but later it included Baltistan into its title, and it was charged with policing and keeping the peace in this highly volatile district.

The militants forced the inhabitants of the Base Camp out of their tents, made them hand over their money, valuables and mobile phones. All of which they then smashed to pieces, and they then tied their hands behind their backs, made them kneel and shot each one in turn. One Chinese climber, Zhang Chuan from Yunnan managed to escape. He ran blindly into the night, zig zagging as he did so followed by a hail of bullets one of which cut his scalp and the bleeding from this was nearly blinding him; fortunately near the camp was a ravine and he dived into this to reach safety. But the remaining ten climbers and a local camp worker all died. Three were from the Ukraine, one from China, two from Slovakia, two from Lithuania, and two from Nepal. One Base worker was allowed to survive by the killers, for he persuaded them he was a ‘good Muslim’. In the early hours of the morning the militants left the camp, and gingerly the Chinese climber returned to his tent where he had hidden a mobile phone. Climbing up towards Camp One, he managed to make contact with those in residence there and let them know what had happened. They summoned help and later that day the Pakistan military arrived in helicopters. The climbers in the high camps then all retreated and assembled at the Base. Initially the idea was to walk out, but worried that the militants would still be in the area they refused, and eventually they were flown to safety.

Subsequently the Pakistan Taliban claimed responsibility for this attack, but unlike the climbers who reported they believed this had been carried out to avenge the death of Bin Laden; they stated it had been in retaliation for a USA drone strike, which had killed a local Taliban leader, Waliur Rehman. The whole area around Nanga Parbat is fraught with tribal loyalties and long standing disputes, but this attack on the climbers was seen by the Pakistan authorities as truly serious, and almost the very next day it was the subject of debate in the countries legislature. An enquiry was set up and an Army Colonel, Captain and Police officer were despatched to investigate. But they too met a bloody end, gunned down in a hail of bullets in their car at Chilas, a nearby town on the Karakoram Highway, again being the victims of the Taliban; however they had managed to establish that the militants were mainly local before their demise.